I’ve been struggling to find the motivation to write new things for a few months now. In trying to diagnose why , I landed on a particular reason why it might feel particularly difficult for screenwriters to create their own new work right now (other than “you probably have ADHD” - let’s just take that as read). If you’re also struggling to write right now too: let me try and save you a few hours of introspection.

If you happen to be a screenwriter, I’d wager you also happen to be under-employed at the moment - and I’m only gonna feel slightly bad about collecting my winnings from you, because I’m also under-employed right now. You shouldn’t have agreed to the bet, idiot!

So: perhaps you have more hours at your disposal than usual right now, and you’re on the hunt for your next job. It’s obvious what you should do: write your hot little sitcom pilot! Or that sweet idea for a crime thriller miniseries! Use all those lovely hours you have to create your next opportunity!!!

But you already know that’s what you should be doing. The question is: why is it hard? Yes, writing is tough. But… you’re a writer! Isn’t this what decided to base an unhealthy proportion of your whole identity around? The only thing you need to do to be a writer is to write things. Why are you dicking around reading Substack? FEEL GUILTY! LET THAT GUILT COMPOUND INTO SELF LOATHING. DO NOTHING PRODUCTIVE FOR THE REST OF THE DAY. PLEDGE TO YOURSELF THAT YOU’LL DO BETTER TOMORROW. IGNORE THE VOICE THAT WHISPERS “YOU WON’T”.

When did you last feel something

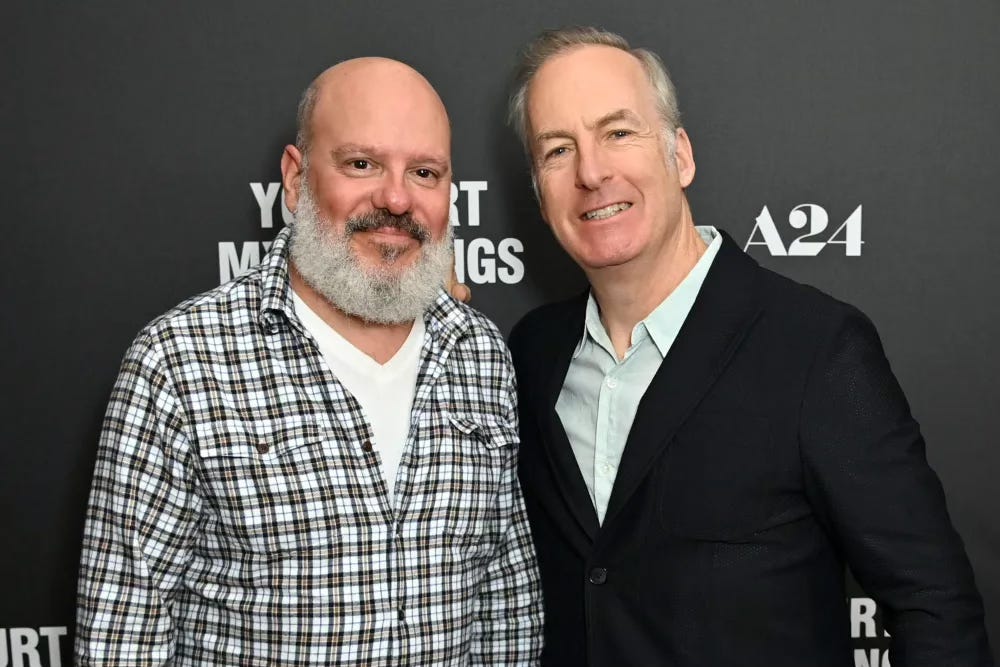

I asked myself when I last felt like I was being “successfully” creative outside of the work I’m paid to do. For me, there were two recent examples: one being a feature film script I’m outlining with my writing partner in London at the moment, and the other being when I wrote MURDER FOR DUMMIES.

If you’re already subscribed to this newsletter, chances are you know about my silly little indie comedy-horror series. If you don’t: it’s my silly little indie comedy-horror series. Writing six episodes wasn’t always easy, but I was able to commit to getting my arse in the chair and getting it written. So why am I struggling to do something that’d be 1/6th of the workload? What is it about that project - and the feature I’m writing with my friend - that makes those easy, when everything else feels hard?

There’s an easy answer to settle on, if you want to duck out of reading this early: writing something that’s meant to be a calling card for you as a professional writer comes with a lot of pressure. Maybe you’re torn between writing the kind of versatile, catch-all, easy-reading, mildly-funny script that execs and studios and managers and agents claim they want - or following the advice that says “write the script that’s pure YOU!” Maybe, like me, you have a handful of ideas for things you could write, all sitting somewhere on that spectrum, and you’re feeling a little decision paralysis.

But… it’s not just that, is it?

If that’s all it was… we could just pick one. I did just pick one. But it felt like either way, I was making the wrong choice. Either I can write the more versatile, “industry-friendly” choice - and sure, give it my voice, make it my own, find what makes me love it and connect with the characters - or take the easier route and go for the big, weird, idiosyncratic, unabashedly “me” idea. It doesn’t need to sell - it just needs to show my voice. It needs to demonstrate what I can do…

…to industry people.

And that’s what it is, isn’t it? What it actually is. That’s why either choice feels so inherently dissatisfying.

Ask yourself the question I asked when trying to get to the root of all this:

What drives you to write in the first place?

I’ve written before about why I believe that what people are calling “AI” can’t actually replace writers: it doesn’t have a perspective or a point of view, and therefore it cannot express anything. Whether you write or paint or sketch or sculpt or carve or compose - the compulsion to make art is inherently about both exploring and expressing who we are as people. This is why all artists make things: because we’re compelled to try and understand something about ourselves, and then we want to share it with people and go “hi you feel like this too maybe?!?!?”

But there’s something about writing a screenplay specifically - perhaps uniquely - that directly clashes with what it means to express yourself creatively: it’s a form of creative expression that is fundamentally incomplete until it’s turned into a film. In order to actually express your ideas to the wider world, you are inherently dependent on the resources and permission of others in the way that novelists, painters, musicians or sculptors simply are not.

This isn’t to say that artists of other disciplines don’t need resources, or are exempt from dealing with the “industry” when they’re at a professional level - hooray for capitalism! - but creators in every other medium I can think of can finish their chosen work without being dependent on others the same way a screenwriter is. You can finish your novel, or perform the song you wrote, or finish your painting; regardless of whether or not it sells, or how many people read it, or how good it is, it is complete. It exists in a finished form, ready for public consumption. Who is your newly finished artistic work for? Why, it’s for whoever wants to look at it! It’s done!

But who’s your screenplay for? Who’s your audience?

It’s studio executives. It’s agents and managers. It’s - if you’re lucky - potential collaborators, other artists. And… that’s it. That’s the whole scope of your audience.

That’s who you’ve limited your audience to, as an artist, by writing a screenplay. Your creative expression is for a tiny audience of people: all of whom are increasingly beholden to tHe AuDiEnCe DaTa. The result is an increasingly narrow definition of what a successful series or movie might look like, instead of anyone going off their instincts or taste. And these are the people who need to connect with what you’re doing enough to invest millions of dollars and thousands of hours into sharing your story with the wider world.

What are we realistically talking about here? A hundred people max? Fifty? Thirty? Is that what you want to limit your artistic expression to? How can that be an accurate gauge of whether what you’ve made will find an audience?

Don’t get me wrong: if fifty people all tell you your script sucks, then it probably does suck (sorry, John). But - as we keep seeing again and again, from Marvel and Star Wars failures to big-name actors openly talking about struggling to get their projects made - the TV industry’s over-reliance on data when it comes to commissioning has led to the fundamentally stupid, impossible pursuit of surefire hits at all costs. That’s why there’s so few shows and movies that aren’t based on an existing IP right now - because there’s data to back up that approach!

Except studios are unable to prevent “unsuccessful” shows from existing. There are always going to be hits, and always going to be flops. But like a little old lady tipping thousands of dollars into a Vegas slot machine, sunk cost fallacy has set in: because the numbers tell them that mathematically, they should win if they just stick with what they’re doing, they refuse to acknowledge that there are no guarantees of success.

I am not trying to suggest that studios should be freewheeling agents of chaos who commission projects on a whim and don’t consider a wider audience. But over the last several years, their approach has been taken to an untenable extreme. It has resulted in fewer shows being commissioned, flavourless movies suffering from trying to appeal to the broadest possible spectrum of people, and - most depressingly - a dearth of more idiosyncratic projects that could find a dedicated viewership if the studios were willing to bet smaller. This has had a particularly outsized impact on comedy.

Before I became a screenwriter, I wrote plays and comedy sketches and weird hybrids of the two, and I produced them and put them on stage with my Casual Violence boys, and got them seen by hundreds of people. Not everyone liked what we made, but enough people did that we were able to connect with, build, and sustain an audience throughout our time as a live act.

What makes me nostalgic for Casual Violence’s heyday was the satisfaction of actually making things. Our shows weren’t just scripts, they weren’t requests for permission to create: they were finished products that we proudly shared with the world. Our shows were specific and strange and silly - our breakthrough hit was a surreal Gothic comedy about a villainous family with a tradition of taxidermying their ancestors - but our audience did exist. They were out there - and they found us because we put ourselves out there too.

There’s been a trend in TV and movie commissioning lately where comedies are being produced far less regularly than they used to be - even though audiences often respond very well to it. I think the reason studios are becoming increasingly comedy-averse is that humour is too specific to be defined by an algorithm. Not everyone finds the same things funny! There’s so little comedy that can be broad enough to appeal to everyone - and even comedies that seem too specific or weird can usually connect with a broader audience. Comedy should be idiosyncratic - it should be driven by the freakish perspective of some oddball weirdo who sees the world in a way that it feels like only they could have thought of…

…because the truth is, it’s never something only they could have thought of.

That’s why writing MURDER FOR DUMMIES was one of the last times I felt that drive to create. We decided right from the beginning that we’re not going to ask permission to make it: we’re going to make it, and no matter what, we’re going to release it. We’re not going to say no if someone drives up to our houses with a truckload of money to licence the series (so if you were on the fence about doing this - go for it!) - but we’re choosing not to depend on others to express ourselves creatively. We know our audience is out there.

Making your own work isn’t easy, and I don’t mean to imply that it is. I recently did a unexpectedly viral Twitter thread about how the general creative advice to “just make your own film!” overlooks the kind of privilege and resources required to actually do it.

Yes, you should probably write your all-important “hire me!” script write now if you can (sorry). But if that idea feels inherently off-putting: maybe it’s time to draw a line between the scripts you write for your job, and the art you make.

J.

My writing is entirely different to yours James but this is just what I needed to read to pick up "the pen" Thanks!