#3: outline, dummy!

the importance of outlining when writing stories - even when you don’t do it

To write a murder mystery, you must be more fiendish than your murderer, and more cunning than your detective.

You have to plan your story so intricately that your audience can theorise without getting ahead of you. They have to stay only one step behind your detective. And, maybe more than any other genre (come at me), the ending has to hit that sweet spot of being surprising yet inevitable: a pay-off that doesn’t feel like you’ve been cheated; one that makes you go “of course!” instead of “wait, what?”

All this considered: you should definitely write an outline of the whole story before you start a whodunnit.

So why the fuck did I write three episodes of Murder for Dummies without having a finished outline?

A surprising amount of screenwriters seem to resent outlining. They crow about Stephen King - or the Breaking Bad writers, who gave Walt a machine gun without any idea what he was going to do with it. By painting themselves into a corner, they’re forced to come up with more inventive, more creative solutions, apparently.

Personally, I think this is bollock-brained.

When I started out writing shows for Casual Violence, we didn’t plan our pay-offs. Our grotesque, heightened characters gave us freedom to take big narrative leaps. But our approach still had its limits.

House of Nostril, our first show with a central story arc, had a wonderful ending - but it took me and our show director days of being stuck in an office, bashing our heads against the wall almost literally, to find it. I’d written 80% of a good show, but without the ending we came up with, the whole thing would have landed like a lead balloon (ie: lots of questions about why we even bothered making a balloon out of lead in the first place, how stupid we were, etc).

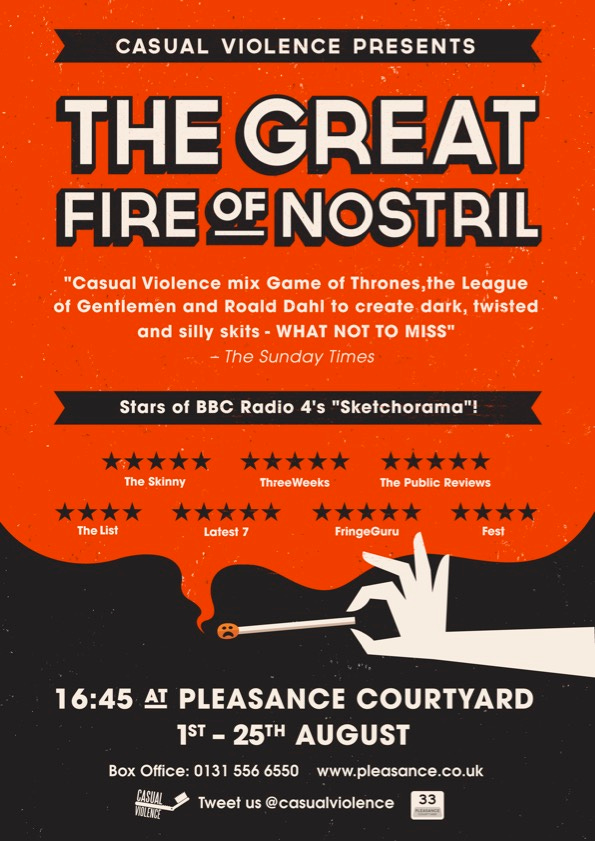

Our follow-up, The Great Fire of Nostril, was the most excruciating writing experience I’d ever had.

The title came from our original pitch: how our evil Nostril family were responsible for the Great Fire of London. But a month before the Fringe: our story had completely changed, I only had two-thirds scripted… and no idea how we were going to put a bloody fire in.

There is no better way to learn the value of outlining than seeing what happens when you make something without one.

Becoming a professional screenwriter was the first time I was required to outline. Once you get into this job for real, it's a non-negotiable skill - and learning on the job taught me the benefits.

I don’t understand why it’s surprising to some writers that - like a picnic, a wedding, or a round-the-world trip - it makes sense to plan in advance. It may seem more romantic to improvise, but it’s going to feel a lot less romantic when your picnic’s just a handful of Sainsbury’s scotch eggs, you forgot the bottle opener, and your blanket’s made out of kitchen roll.

There’s two reasons I think the anti-outliners are stupid. First: outlining is writing.

Guess what: you’re still being spontaneous and creative! You still have to come up with solutions out the blue, and rewrite things that don’t work! You can even write dialogue if you want to! All the things people claim outlining robs them of are exactly the things an outline is for, except you have far fewer pages to fix if you spot a problem. I know writers love to self-flagellate, believe me, but there’s really no need to give yourself more work than you already have.

Not only are you saving yourself time and likely heartbreak, but when you sit down to write the first “real” draft: it will be easier! You won’t hit as many walls. Yes, you might still hit occasional obstacles you need to devise unexpected solutions for…

… but this is the crux of Reason Two: your outline is not set in stone.

I read something years ago - I think from Chuck Wendig? - that described your story as the woods, the plot being the path you take through the trees, and the outline as your map. Obviously, having a map can - and will! - save you from getting lost...

…but if you’re in amongst the trees and you see something interesting, just off the route you intended to take? Follow it! Whether it’s a dead end or a game-changing discovery, having your map means you’re freer to explore. You always have your path to return to. You know where you need to end up.

Okay, Mr I-Love-Outlining… why didn’t you do it before writing Murder for Dummies?

Well: truth is, I did! Sort of. Kinda. A lil bit. But not enough.

When we began development meetings, we talked through the archetypes you normally see in true crime documentaries and whodunnits, and explored possible motives they’d want our victim - a famous ventriloquist - killed. We delved into our victim Keith’s backstory too, creating a loose timeline of his life before his murder.

MINOR SPOILERS FOR “MURDER FOR DUMMIES”:

Above are a few screengrabs of that first, early Google Doc. There’s snippets of the first ideas we had for characters - some of which made it into the show once I fleshed them out and developed them at script.

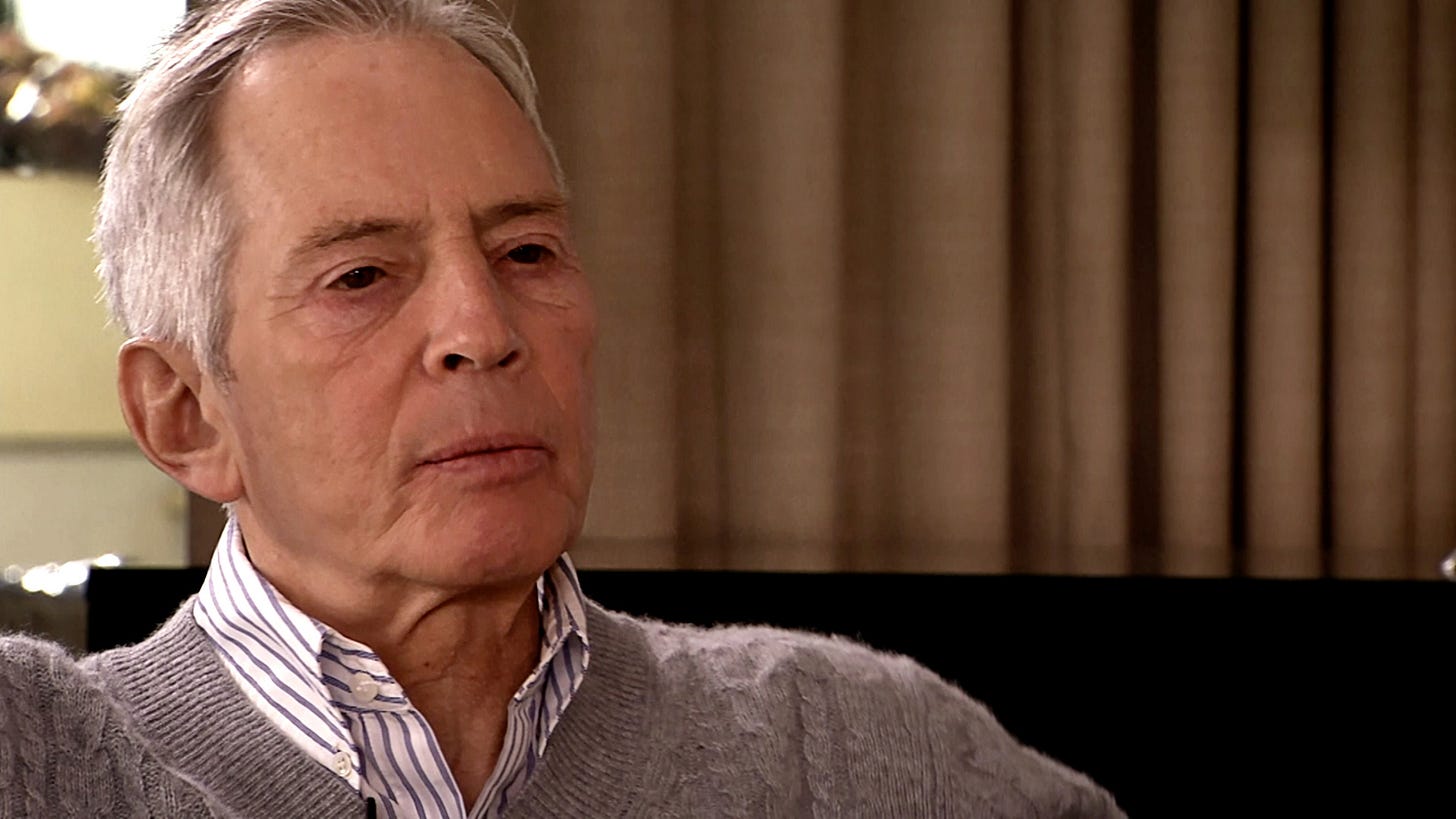

One favourite of mine’s up there: I’d recently watched The Jinx, and I was talking through the absurdity of how Robert Durst’s friends think he’s a lovely guy even though (and you hate to say it, but) he looks and acts SO MUCH like a murderer.

I asked if anyone had pitches for a character like Durst; Alex suggested our rich and famous victim might have had a “live-in butcher”, and Molloy Mangle was born. We shot his scenes in October - here’s our best boy Greg as Molloy.

At the beginning of development, I had come in with a pitch for which character the murderer should be (no spoilers)… but it was months before I properly solidified their motive and means.

What I should have done before writing the first episode was write a full story document, detailing how all our characters spent the months and minutes prior to Keith’s murder. Not only that, but there also needed to be a rundown of everything between the murder and the beginning of the documentary twenty-three years later.

But I hadn’t done any of this yet. I did have a loose outline for episode one: a map sketched on the back of a napkin. I had the brainstorming document - but that’s it.

And yet I blindly launched into script anyway. The group liked it! Our director liked it! I liked it! So I dove straight into the second episode - again, with only a loose bullet pointed episode outline as a guide for structure. But hey, this episode was “motive”, and we’d already figured out Keith’s backstory! Easy!

It was after I’d done the third script that I realised the error of my ways. It was sluggish, dense, plotty - because I didn’t have a clear enough idea of what needed to be in the episode. Our show relies on every interviewee being a suspect, meaning I needed a concrete, full timeline for the night of the murder…

…which I didn’t have. And couldn’t do yet, because I still didn’t know for sure why the murderer had done it in the first place.

I was lost in the woods. I had to go back, retrace my steps, figure out where I’d gone wrong - and draw the fucking map.

I still feel like I should have approached writing the show differently. But here’s the thing: when I have to outline for television, the characters have already been figured out. To switch metaphors mid-stream: I’m given the Barbies to play with, and their Dream House has already been built.

I think the mistake writers make by refusing to outline is that, like a stubborn dad on a road trip, they’ll refuse to admit they’re lost. They’ll wander around, wasting time and energy - usually until they stop writing, the project never gets finished, and they die out there in the woods. (RIP dad, miss you every day xxx)

But diving in early meant I found the voices of the characters, wrote jokes that would inform major plot points, and found the tone. The characters weren’t characters yet. They were brainstormed bullet points. They didn’t come alive until I heard them speak.

Murder for Dummies would have never worked if I didn’t go back and outline. But one thing I learned writing this show is that, as long as you’re sure you know how - and most importantly, when - to find your way back… sometimes you can head into the woods without a map.

A good murder, like a good story, should be carefully planned. But you can still get away with an impulsive crime of passion.